Understanding climate change denial

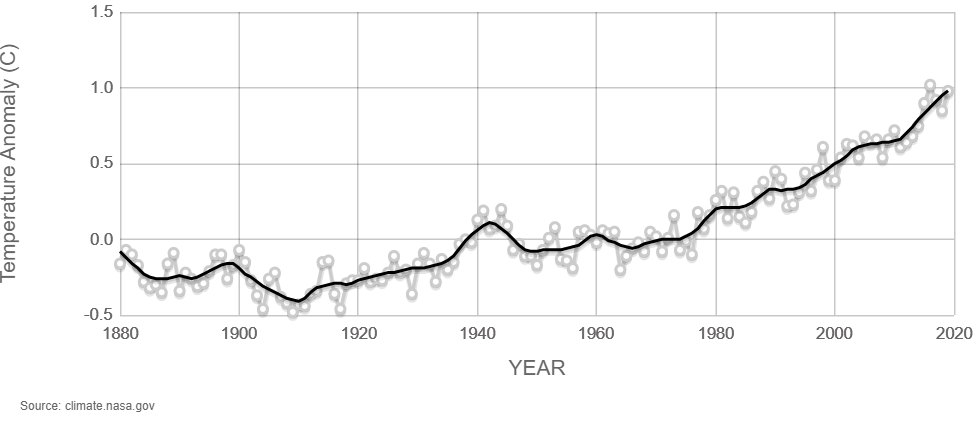

Since 1880 human activity has caused the average global temperature on Earth to increase by approximately 0.8° Celsius. This straightforward assessment, often referred to as anthropogenic climate change, is agreed to by at least 97% of climate scientists. What’s more, this appears to be a conservative assessment. One peer-reviewed paper puts the level of consensus among scientists as high as 99.94% and points out “it is hard to think of a case in the modern era in which scientists have been virtually unanimous and wrong”. Given such overwhelming consensus, it’s hard to understand how climate change denial has gained so much traction. Research conducted by The Australia Institute in September 2018 found only 76% of Australians accept the reality of climate change, while 11% do not think climate change is occurring and 13% are unsure. Americans are more sceptical, with only 62% agreeing with the proposition that humans are primarily responsible for climate change and 23% saying it is due to natural changes in the environment (according to Yale). This is despite clear evidence that man-made climate change has been underway since 1950. The evidence that global temperatures are rising is now irrefutable: the five hottest years on record were the last five years, and 18 of the 19 hottest years have been since 2000.

How has climate change denial thrived in the face of such undeniable evidence? The media must accept some of the responsibility along with overly cautious climate scientists. The rise of populist leaders around the world has also been a factor, as have conspiracy theories propagated throughout the internet. Underpinning all of this has been an intense lobbying effort by the fossil fuel industry.

The role of the media

What appears in the online and print media plays a vital role in shaping popular opinion about climate change.

False equivalence

One of the first things new journalists are taught is to provide their readers with ‘balance’ by always giving equal weight to both sides of the story. While this is an admirable principle in theory, it risks legitimising fringe viewpoints. If a reporter gives equal weight to a climate change denier in a misguided effort to be ethical, the inference drawn by the reader will be that anthropogenic climate change is something that is up for debate. The reality, of course, is that the science on climate change is settled.

Where did all the science journalists go?

Mainstream science journalists are becoming a thing of the past, according to Sydney University public health expert Emeritus Professor Simon Chapman. Speaking to Crikey earlier this year, Simon said journalists who cover science and health used to have science degrees which provided a “disciplined interrogation and level of understanding”. These days, he says, time-poor reporters tend to be motivated more by online clicks than accuracy. “It’s driven by the headline now, like finding a breakthrough, or the orthodoxy found to be wrong, or daring scientists and mavericks,” Simon says.

Media bias

Blatant media bias against anthropogenic climate change is one of the more obvious contributors to climate change denial. Our in-house ethics team conducted a review of News Corp (the publisher of The Australian, The Daily Telegraph and the Herald Sun) and found its mastheads exhibit unacceptable bias. This assessment is supported by evidence of lack of editorial independence and exercise of power by controlling shareholders to influence news content to pursue political objectives and commercial interests. A 2013 report by the Australian Centre for Independent Journalism found that between 2011-2012 News Corp publications provided less coverage of climate change than Fairfax (fewer articles, shorter length) in the ‘news’ section. The report found that only 34% of News Corp articles during the period were based on the scientific consensus on climate change, and it also concluded that News Corp tabloids campaigned against (rather than covered) Julia Gillard’s carbon tax.

Timid scientists

Climate scientists must bear some responsibility for the rise of climate denialism. For years climate scientists have used overcautious language for fear of being labelled alarmist. A recent opinion piece in the New York Times titled ‘Time to Panic’ points out the absurdity of this timid approach: “This is a bit strange. You don’t typically hear from public health experts about the need for circumspection in describing the risks of carcinogens, for instance.” Indeed, alarmism seems entirely appropriate given the catastrophic warnings in the latest IPCC report about the effects of just 1.5°C of warming (the report doesn’t even mention 3-4°C of warming, which is the planet’s current trajectory). The New York Times article notes there are signs climate scientists are accepting that it is okay, or even reasonable, to “freak out”. “Panic might seem counterproductive, but we’re at a point where alarmism and catastrophic thinking are valuable.”

Growing populism

The rising tide of nationalist political leaders around the world could not have come at a worse time for the planet. To properly address climate change we need immediate and collective action by the global community. On 1 June 2017 US President Donald Trump announced his intention to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, which will take effect on 4 November 2020. This decision, which is embodied by Trump’s slogan ‘America First’, is disastrous for the long-term health of the planet because the US is one of the largest emitters of carbon dioxide. Trump is a climate change denier himself. Asked about a recent report by his own administration that discussed the economic impact of climate change, Trump said: “I don’t believe it”. Brazil has also elected a populist leader in its new president, Jair Bolsonaro. Within hours of taking office on 3 January 2019 Bolsonaro moved to relax environmental protections that would open up the Amazon – often referred to as ‘the lungs of the planet’ – to powerful agribusiness interests.

Consipiracy theories

The internet is full of conspiracy theories about a sinister group of UN-backed climate scientists cooking up the supposed hoax of climate change. Sometimes, however, these wacky theories make their way into the mainstream – as was the case when then Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s business advisor Maurice Newman wrote an opinion piece for The Australian in 2015. In the article, Newman said climate change is “about a new world order under the control of the UN” that seeks to make “environmental catastrophism a household topic to achieve its objective”. Such views are relatively harmless in the depths of the internet but quite dangerous when legitimised by a broadsheet newspaper. Other conspiracy theories about climate change include claims that IPCC climate scientists are making piles of money (in fact, none of them are paid by the IPCC) as well as claims that climate change-denying scientists can’t secure funding. The latter claim is absurd and betrays a fundamental misunderstanding about the scientific method, which constantly tests hypotheses by attempting to falsify them. If a climate scientist had credible evidence the consensus on climate change was wrong they would become a minor celebrity overnight; in reality, papers about climate change denial are almost never published.

Fossil fuel lobbying

Finally, the big one. Just as the tobacco industry denied the link between cigarettes and cancer long after the science was undeniable, the fossil fuel industry has worked steadily to undermine climate science for decades. As far back as 1979 oil producers like Exxon and Texaco knew about the effect of climate change on the planet, according to memos uncovered by Greenpeace USA. In the following decades Exxon and other oil producers worked to manufacture uncertainty about climate change, says Greenpeace. Similar efforts have been made to promote climate denialism in Australia. Billionaire and Australia’s richest person Gina Rinehart, who owns Hancock Prospecting, donated $4.5 million to the climate change-denying Institute of Public Affairs throughout 2016 and 2017. Rinehart, a climate change denier herself, also supported the speaking tour of British climate change denier Lord Christopher Monckton. Geologist and climate change denier Ian Plimer sits on the board of Hancock Prospecting.

What can you do?

Climate change deniers tend to be pretty certain about their views so it can be difficult to change their minds. Somewhat depressingly, there is evidence that citing more facts can make them even more entrenched in their denial. Our Head of Ethics Research Stuart Palmer recommends appealing to the political conservatism of climate deniers by talking about ideas like carbon capture and geoengineering (ie, new technologies that could reduce the amount of carbon in the atmosphere without requiring a collective global effort). Ultimately, one thing we can all do is support organisations that are working to combat climate change. That includes making sure your money is invested in a carbon-free future.